Garden tour

Carl Linnaeus purchased Hammarby in 1758. Here the members of the Linnaeus family spent their summers and here Linnaeus could grow plants which did not thrive in the often too moist soil of the Academic Garden in Uppsala.

What to see in the Gardens

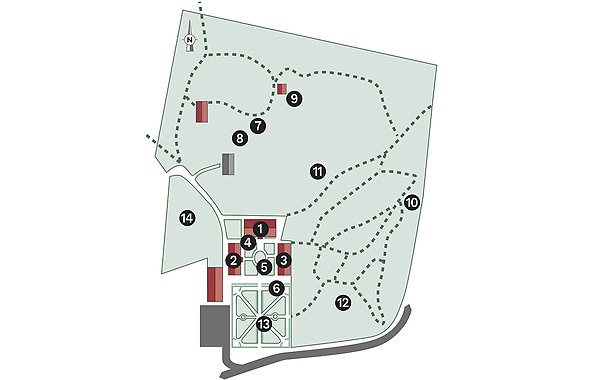

Use the map or the links in the list to learn more about the sights at Linnaeus' Hammarby.

1. The Manour

The main house at Hammarby was commissioned by Linnaeus and completed in 1762. Here portraits of Linnaeus’ family, friends and pets and, above all, of Linnaeus himself can now be seen. There are also numerous objects that belonged to the Linnaeus family, ranging from a lemon squeezer to tablecloths and clothes. Linnaeus’ study and bedroom are decorated with hundreds of beautiful prints of flowers which he had pasted to the walls instead of wallpaper.

Wall papers, house contents and virtual tour

Come along on a 360-degree virtual tour of the dwelling house at Hammarby. Choose Street view.

The National Property Board, which manages the manor, has written an article about the flower prints in Linnaeus's study and bedroom.The article "Lustgården på väggen blomsterplanscherna på Linnés Hammarby" is only available in Swedish.

The Art Collections of Uppsala University are responsible for the furniture, artworks, clothes and other objects at Linnaeus Hammarby.

2. The West Wing

The detached west wing was the Linnaeus family’s first home at Hammarby, while they waited for work on the main house to be completed. After that it was probably occupied by one of the tenants who farmed the estate.

Today an exhibition about Linnaeus and Linnaeus’ Hammarby can be seen here.

3. The East Wing

The detached east wing is roofed with turf, as it probably was in the 18th century. In 1753 Linnaeus described how the roofs of houses in Uppsala were covered with green turf. Roofs of this kind supported a special flora, made up of plants tolerant of poor, dry habitats: drooping brome Bromus tectorum, orpine Sedum telephium, biting stonecrop Sedum acre, narrow-leaved hawksbeard Crepis tectorum and star (or twisted) moss Tortula ruralis. Linnaeus gave several of them the name tectorum, from the Latin tectum meaning ‘roof’.

In the province of Småland where he grew up, Linnaeus had seen peasants planting common houseleek Sempervivum tectorum on their turf roofs to protect their cottages from fire. Around Hammarby another species is found, hen-and-chickens houseleek Jovibarba globifera, which has spread from Linnaeus’ gardens. He may also have planted it on the turf roofs of the simpler buildings here.

In Linnaeus’ time, the east wing served as a brewhouse and bakery

4. Linnaeus' Flower Beds

In front of the main house are two flower beds, one on either side of the door. They have been recreated from a sketch made by Linnaeus himself in the 1760s, showing which plants were grown here and how they were arranged in the beds.

5. Siberian Crab Apple

In the open courtyard in front of the main house is a Siberian crab apple Malus baccata that has been growing here since the 1760s. When it blooms at the end of May, this aged tree is an impressive sight, draped in large white flowers. The apples are very small, however, and Linnaeus and his son recommended the species primarily for hedges and as grafting stock.

Linnaeus was probably given seeds of Malus baccata by the Finnish natural historian Erik Laxman, who served as a clergyman in Siberia around 1765. There were originally two trees of the same age here, but one of them fell in 1850 and has since been replaced with a graft from the surviving tree. Linnaeus seems to have taken quite a liking to the Siberian crab apple, and also used it for hedges in his garden. Remains of them could still be seen in the 1830s

6. Russian Pea Shrub

The hedge marking the south side of the courtyard is planted with Russian pea shrub Caragana frutex, as it was in the time of Linnaeus. The shrubs now growing are descendants of the ones Linnaeus raised from seed in the 1760s. Behind the east wing is a relative of the Russian pea shrub, the Siberian pea tree Caragana arborescens. It, too, can be traced back to Linnaeus’ plantings at Hammarby.

Linnaeus was concerned about the large numbers of young spruce trees being cut down in Sweden to build fences, and about the cost involved. He was therefore keen to find plants that could be used for hedges – ‘living fences’. These two Caragana-species are among the ones he recommended as hedging plants.

7. The Siberian Garden

On the rocky slope leading to the natural history museum, an open site has been cleared. This is what remains of the Siberian Garden, or Hortus Sibiricus, which Linnaeus had laid out to accommodate a large consignment of Siberian seeds that he received in 1773 from the Russian Empress Catherine II.

Linnaeus was keen to introduce new plants, useful and ornamental, that could cope with the Swedish climate. Consequently, he was particularly interested in species from North America and Siberia. A similar ‘Siberia’ was created in the Botanical Garden in Uppsala. Having plants growing in two places was practical for the ageing Linnaeus, as it meant that he always had them close at hand. We do not know what species were grown in the Siberian Garden, but they probably included hen-and-chickens houseleek Sempervivum globiferum and rock cinquefoil Drymocallis rupestris, both of which are found in the area to this day.

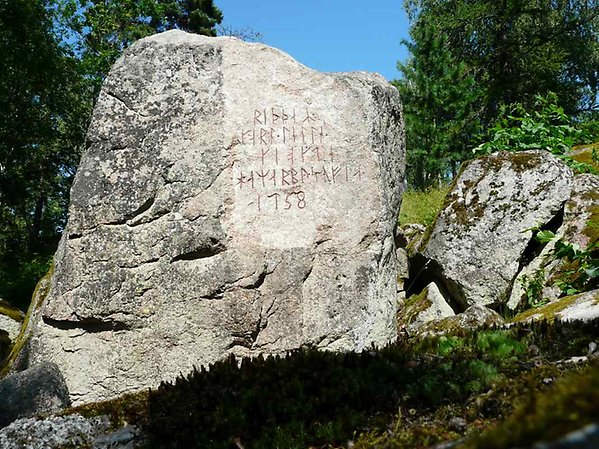

8. Linnaeus' Rune Stone

Carved into this large boulder is a runic inscription:

Sir

Carl Linnaeus

purchased

Hammarby-Säfja

in 1758

Linnaeus bought the two estates of Hammarby and Sävja in 1758 and had this inscription made to mark the occasion. It was not unusual in the 18th century for scholars to have texts carved in runes as evidence of their learning. Linnaeus was fascinated by runic writing, and recorded many rune stones on his travels around Sweden.

9. Linnaeus' Natural History Museum

At the highest point in the park is Linnaeus’ natural history museum, built in 1769. ‘My palace in heaven’ is what he called this little stone building. Here he kept his natural history collection, safe from the dangers of fire and flood. Outside the museum he also taught his students, a fact recalled by the strange piece of furniture known as the ‘plugghäst’, or ‘study horse’.

The great fire that had swept Uppsala in 1766 had come very close to Linnaeus’ house in the Svartbäcken area of the city. It had reminded Linnaeus of an earlier blaze in 1702, in which his predecessor Olof Rudbeck the Elder had seen his great herbarium and his flora project Campus Elysii go up in smoke. For fear of fire, Linnaeus no longer dared keep his natural history collections in town. He therefore had this small building constructed, in stone and with no fireplace, at a safe distance from the main house.

The museum was opened on 21 May 1769. Two months later, Linnaeus wrote in a letter to his friend Abraham Bäck: ‘I am now lying in my summerhouse on my high hill, delighting in my old age in the fresh air, the prospect [view], my natural specimens and the innocence of country life.’

10. Linnaeus' Grove

‘Keep alive in your own day

the grove that I have planted,

and if any trees be lost, plant others in their place.’

This request by Linnaeus to his wife Sara Lisa is quoted from a list of things he asked her to take care of after his death. The grove he was referring to was probably this area by the road to Hubby. There is believed to have been a square arbour of trees here, known to his grandchildren as ‘Grandpa’s leafy bower’. A quiet spot where Linnaeus liked to sit and smoke his pipe, and where dinner would be served when the weather permitted.

According to family tradition, Linnaeus’ four daughters each had a ‘plum grove’ at Hammarby. In the now overgrown garden, vestiges of Linnaeus’ orchard can still be seen, including plum Prunus domestica, dwarf cherry P. cerasus and gooseberry Ribes uva-crispa.

11. The Hill (hammer)

The name Hammarby is known from the 14th century and comes from the Swedish word hammar. In 1679, Olof Rudbeck the Elder explained the meaning of the word as follows: ‘A hammar is a rocky, wooded slope’. Hammarby thus takes its name from the steep, boulder-strewn hill that juts out like a headland on the flat plain.

The hill was within the boundaries of a Crown forest area where Linnaeus was allowed to graze his livestock. As a result, it was not as thickly wooded in the 18th century as it is now. Linnaeus chose the top of this hill as the site for his natural history museum. From there he had a magnificent view of the plain, and the museum could be seen from far around.

12. The Park

Behind the main house is a wooded park, with paths winding beneath the trees, among boulders and carpets of martagon lily and dog’s mercury (Mercurialis perennis L.).

On maps from the 17th and 18th centuries, this area is marked as a garden. Originally it was only used as an orchard, but when Linnaeus moved to Hammarby he also had Swedish and foreign species of interest for his research and teaching planted here.

After Linnaeus’ death, the garden became overgrown and assumed a woodland character, with deciduous trees such as elm, maple and ash. In summer, the sunlight has to filter down through the dense foliage, and only shade-loving plants can survive in the gloom. Among them are several species planted by Linnaeus: martagon lily Lilium martagon, sweet cicely Myrrhis odorata, giant bellflower Campanula latifolia and barrenwort Epimedium alpinum.

13. The Uppland Garden

The Uppland Garden, or Hortus Uplandicus, is a small Baroque garden that was established in the 1880s to show what ornamental plants were grown in gardens in the province of Uppland in the 18th century. The name Hortus Uplandicus comes from a series of manuscripts which Linnaeus wrote as a student in 1730–31, listing plants he had seen in gardens around Uppland, including Uppsala University Botanical Garden and the Uppsala Castle Garden.

The upper part of the Uppland Garden may have been enclosed for cultivation in Linnaeus’ own day, but it is not known what was grown here. When the state bought Hammarby in 1879 this area was a stable yard.

14. The Clonal Archive

In Linnaeus’ day part of this area was a kitchen garden, where vegetables were grown for the family’s use. Today it serves as a ‘clonal archive’ for old cultivars of apples and pears. Linnaeus’ Hammarby is a host site for the Nordic Gene Bank, helping to conserve old varieties of cultivated plants that have to be grown on a continuous basis if they are not to die out.

Here some 30 different cultivars of fruit trees from the Mälardalen region can be studied, including ‘Fulleröpäron’ and ‘Wennströmspäron’ (pears) and ‘Druväpple’ (apple). One variety from further afield is ‘Linnés Stenbrohult’. It was registered under this name at Alnarp and the Balsgård research station in the south of Sweden, and is believed to originate in Stenbrohult parish in Småland, where Linnaeus was born.